Contact information

Research groups

Francesco Boccellato

Leadership Fellow

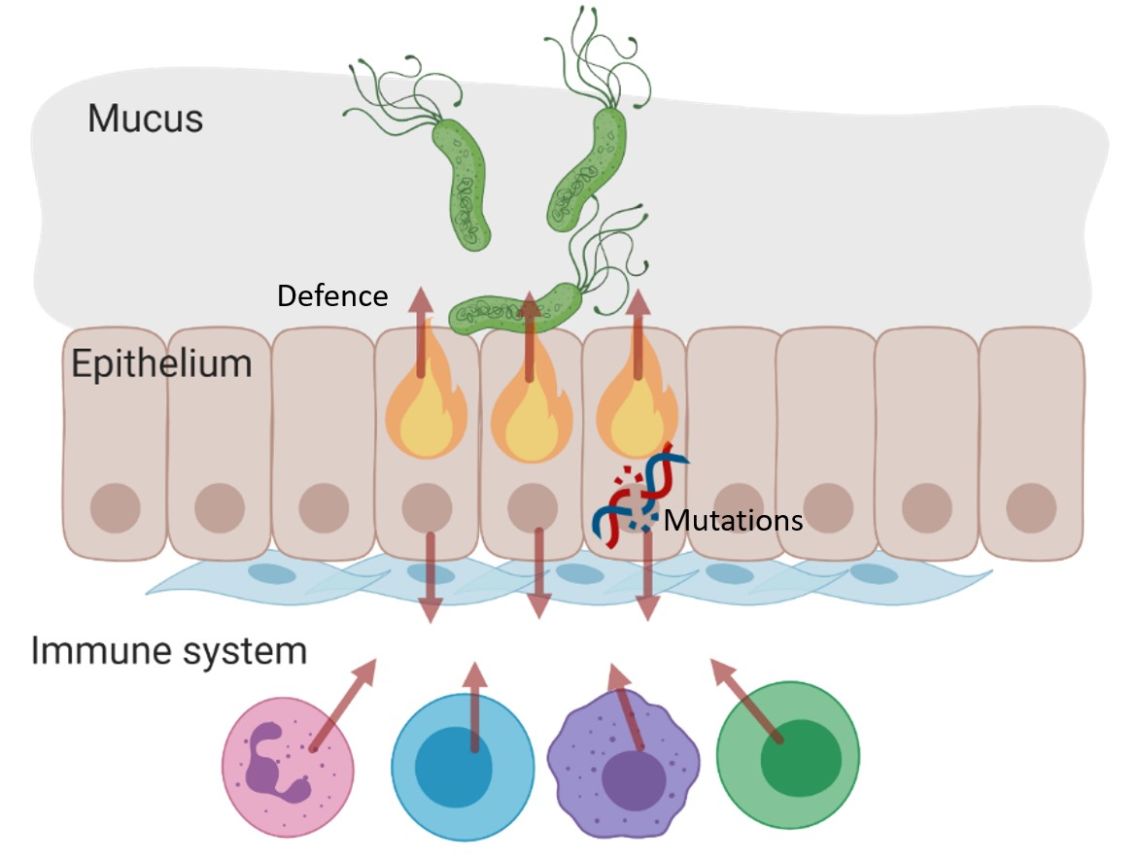

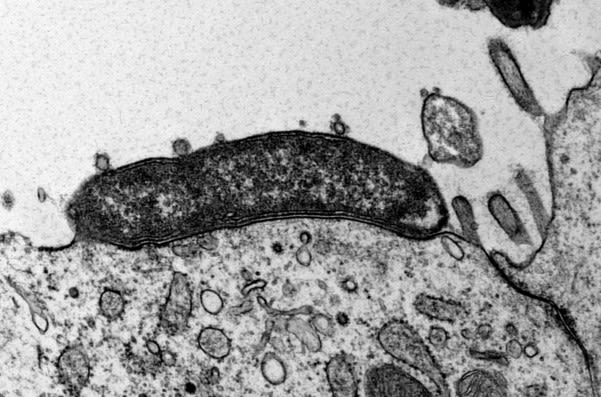

There is strong evidence that some infections represent a major risk factor for the development of cancer, but how pathogens initiate this disease is still unknown and has been the focus of my research since I was a student. During my PhD at the University of Rome (Italy), I studied the Epstein Barr Virus, a herpesvirus associated with many types of blood cancers and carcinomas. In contrast to viruses, bacteria do not transfer genetic information into the nucleus of the host cell and so it remains unclear why bacterial infections are also associated with cancer. Chronic infection with Helicobacter pylori for example, is the cause of most stomach cancer cases. Investigating the direct and indirect effects of carcinogenic pathogens on the host cells tissue is therefore crucial for understanding how cancer begins.

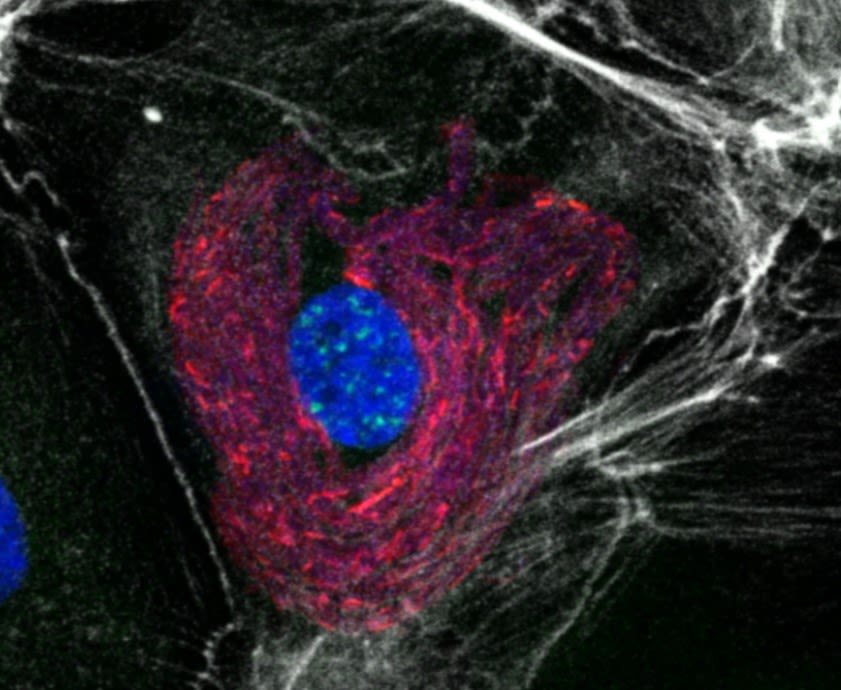

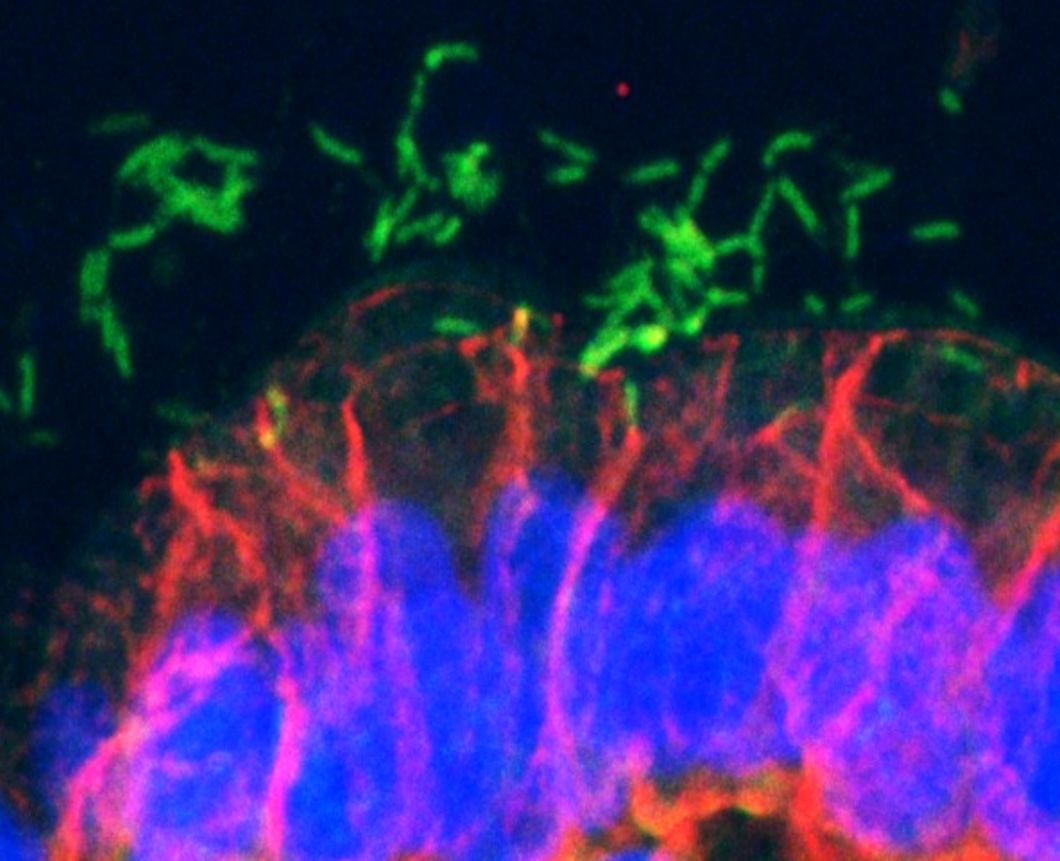

Carcinogenic pathogens can colonise the human body for years, they can change the shape and the cellular content of tissues and they can break the DNA of infected cells, increasing the chances of cellular transformation. To study how pathogens cause cancer we use human derived stem cell-driven culture models and in particular we have invented and patented a primary culture system called “mucosoid cultures”. During my post-doc at the Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology in Berlin (Germany), I generated a model of healthy epithelial cells which faithfully reproduces in vitro most of the features of the epithelium in vivo. The most evident feature of this reconstructed human epithelial layer is the mucus production and its formidable defence capacity against infection. However, some bacteria are able to evade this defensive system and can establish colonies in tissue niches where they can hide from the immune detection for years.

At the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, we are using our mucosoid culture models to study the signals of the tissue microenvironment governing cell regeneration and differentiation as well as the impact of infection on human tissue and the genomes of infected cells. We are actively involved in the development and in the dissemination of human stem cell-related culture technologies because we think that beyond the obvious translational impact, understanding human tissue is a great challenge in biology.

Online seminars

Key publications

-

Inflammation promotes stomach epithelial defense by stimulating the secretion of antimicrobial peptides in the mucus.

Journal article

Vllahu M. et al, (2024), Gut Microbes, 16

-

EGF and BMPs Govern Differentiation and Patterning in Human Gastric Glands

Journal article

Wölffling S. et al, (2021), Gastroenterology, 161, 623 - 636.e16

-

Polarised epithelial monolayers of the gastric mucosa reveal insights into mucosal homeostasis and defence against infection

Journal article

Boccellato F. et al, (2019), Gut, 68, 400 - 413

-

Genotoxic Effect of

Salmonella

Paratyphi A Infection on Human Primary Gallbladder Cells

Journal article

Sepe LP. et al, (2020), mBio, 11

-

Bacteria Moving into Focus of Human Cancer

Journal article

Boccellato F. and Meyer TF., (2015), Cell Host & Microbe, 17, 728 - 730

-

Helicobacter pylori Depletes Cholesterol in Gastric Glands to Prevent Interferon Gamma Signaling and Escape the Inflammatory Response

Journal article

Morey P. et al, (2018), Gastroenterology, 154, 1391 - 1404.e9

-

Genomic aberrations after short-term exposure to colibactin-producing E. coli transform primary colon epithelial cells

Journal article

Iftekhar A. et al, (2021), Nature Communications, 12

-

DNA methylation in human gastric epithelial cells defines regional identity without restricting lineage plasticity.

Journal article

Fritsche K. et al, (2022), Clinical epigenetics, 14

-

Molecular modelling of the gastric barrier response, from infection to carcinogenesis.

Journal article

Traulsen J. et al, (2021), Best practice & research. Clinical gastroenterology, 50-51

-

Morphogen Signals Shaping the Gastric Glands in Health and Disease

Journal article

Zagami C. et al, (2022), International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 23, 3632 - 3632